Queen’s highlights lessons from Belfast flag protest

03 December 2014

Politicians and civil society must learn from the mistakes made during the Belfast flag protest which cost over £21.9 million to police, says a report from researchers at Queen’s.

The Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice has released a report examining the flag protest that took place in Belfast in December 2012 and early 2013 and analysing the lessons to be learned.

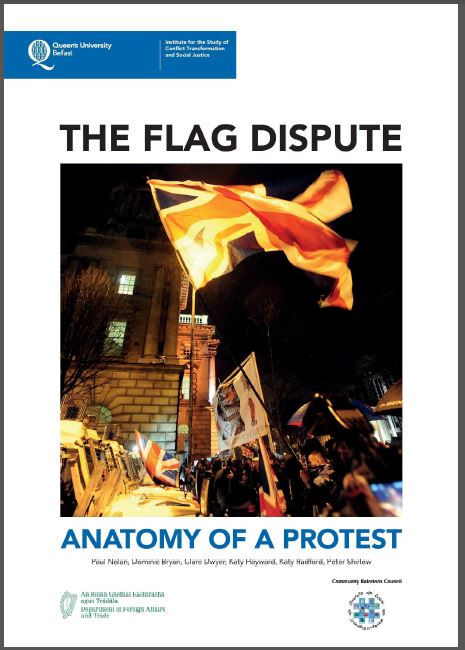

The report, titled ‘The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest’, argues that the flag protest called into question the ability of Northern Ireland’s politicians to resolve political issues within the democratic chambers that are available to them.

Released on the second anniversary of the decision to reduce the number of days the Union flag is flown on Belfast City Hall, the report looks at the origins of the protest, the way in which it developed and spread, the tactics of the police in managing the demonstrations, the arrests and sentencing of protestors, and the political reactions. It also considers the legacy of the flag protest for politics, society, the economy and community relations in Northern Ireland.

Lead author of the study, Dr Paul Nolan said: “The events analysed in the report demonstrate that when politicians fail to find agreement on issues, they do not go away. Instead power “leeches out” onto the streets and the issues re-appear in the form of street protests and public disorder”.

Co-author Dr Clare Dwyer, a researcher at the Institute said: “The threat of criminalisation as a result of engaging in the protests was a great deterrent for many and altered the way the protest continued. But it also motivated others to participate in an effort to ensure protests remained peaceful and orderly.”

Dr Katy Radford notes the particular role of older women in this regard, many of whom were keen to avoid “a repetition of the past”, as they witnessed a new generation of young men resistant to compromise and keen to demonstrate their ‘defence’ of a cultural identity.

Research for the report entailed a comprehensive trawl of print, broadcast and social media, an examination of the criminal justice response, and an overview of change in public attitudes regarding flags, protest and the peace process in 2012/13, plus the creation of a detailed database of all events during the period December 2012 and March 2013.

Bringing together analysis of this data with expertise from various academic disciplines, the researchers present a detailed analysis of the causes and the consequences of the protest.

Co-author, Dr Katy Hayward said: “The causes of the flag protest are in many ways small scale versions of sources of difficulty in the wider peace process. As well as ongoing problems of poverty and marginalisation, we found familiar trends of cultural contestation and distrust of political institutions. In addition to this, powerful emotions - both uplifting and negative - shaped people's experience of the protest and contributed to its lasting impact on individuals and the wider community.”

According to co-author Professor Peter Shirlow, this impact is notably more localised and small scale than that of similar events in Northern Ireland’s troubled past (such as the demonstrations following the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985), and descriptions of a “culture war” are misleading and unhelpful. The root causes of the protest still need to be addressed and the issue of flags and symbols must be handled with care.

Reflecting on the lessons that can be learnt from similar experiences in Northern Ireland’s history, the report highlights cases when differences over symbols have been resolved successfully and advises that this type of creative thinking will be needed in the future.

For example, the report notes that the choice of a symbol for the Northern Ireland Assembly could easily have turned into a bitter argument. Dr Dominic Bryan suggests: “Instead, a piece of creative thinking resulted in the adoption of the flax motif, now accepted by all sides as an elegant symbol for the devolved parliament.

“This is the type of creative thinking that will be required in the future. There will be other symbolic issues which could ignite similar passions. The politicians and civil society have a duty to work together to make sure that that they do not. That means they must do more than simply express grievances; instead they must work to find solutions.”

As a fresh round of party talks tackles the contested issue of flags and symbols, this research is a timely reminder that this is a matter which can be resolved with political will. Moreover, prolonging disagreement on that issue covers the deeper causes of conflict and hampers the effectiveness of the enormous efforts in peacebuilding and reconciliation that are continuing despite political impasse.

The full and summary reports can be found on the Institute website. A print version of the report will be launched by Queen’s in January.

For media inquiries please contact Andrew Kennedy, Queen’s University Communications Office, andrew.kennedy@qub.ac.uk 028 9097 5384.

Back to Main News

Top of Page