How do you bring a whole community to the table? How do you ensure people of all backgrounds are represented? And what does it mean to really listen – to everyone? We asked three of Queen’s leading experts.

What does it mean to be inclusive? Can you insert cohesion into a broken community? And what happens if you can’t? In Northern Ireland, community has long been an essential consideration – but around the world, what it means to belong, to be heard and to be represented are rapidly becoming vital questions as we consider how to ensure our democracies remain strong and vibrant.

Dr Fiona Murphy, Senior Lecturer in Anthropology at the Senator J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice says that recognising identity – and historic loss – is only the first step.

Between 1910 and the late 1970s, large numbers of Indigenous Australians were removed from their families and adopted by white families, as part of Australia’s white assimilation policies. Many of these people were Aboriginal Australians who had mixed parental heritage. They are now known as the ‘Stolen Generations’.

The purpose of removal, in line with Australia’s white assimilation policies, was genocidal in intent: voiced as an attempt to ‘breed out’ Aboriginality. The authorities went to great lengths to achieve this separation – children were moved across states, with no way to find their way back to their families. Sadly, these policies were not unique to Australia: they were enacted throughout the colonial project, in the US, Canada and even Scandinavia.

My grandfather was in an industrial school in Ireland, and while that was a very different context, I’ve always been interested in the experience of removal and institutionalisation; much of my work is with refugees and their experiences of displacement and dispossession. In Australia, I work very closely with a community of Aboriginal Australians who have experience of removal. It was, and remains, a huge privilege as an anthropologist to get to know them and observe the everyday experiences of their lives – to hear their stories, and try to bring them to a wider audience.

The Stolen Generations see themselves as a distinct community, sometimes quite separate from Indigenous people who weren’t removed, and separate from white Australians. They are each other’s family – they talk about being brother, father, sister and mother to each other. But they are also a community of loss. This in itself is hard: how do you move forward when your identity is anchored in trauma?

While some of the Stolen Generations have managed to reconnect with their Indigenous families, it is too late for many of them in terms of creating an emotional attachment. The harm is intergenerational, too. Today, there is an extremely high rate of removal of Aboriginal children. That is down to intergenerational trauma and continual inequalities for Indigenous Australians.

These issues are, finally, being talked about more. There’s a lot of conversation right now around Indigenous politics and movements towards self-determination – there’s also an intersection here with the debate on whether Northern Ireland should have its own Truth and Reconciliation committee.

The Stolen Generations campaigned successfully for an apology and for reparations but, overall, the Australian government’s official response thus far has been very piecemeal. I hope that my work can help to highlight people’s experience of how they navigate trauma and institutionalisation, both individually and collectively, and how this impacts and fractures communities. That is a great place to begin in order to explore how to remedy these harms.

Paul Stapleton, Professor of Music at the Sonic Arts Research Centre, says that understanding has to begin with listening. Hard.

This story starts when writer Shannon Yee, a New Yorker living in Belfast, woke up with what she thought was a sinus infection. By the end of the day, she was in the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast being treated for a rare brain infection: subdural empyema. Anywhere else in the world, she would probably have died – but one legacy of the Troubles is that the Royal has particular expertise in dealing with head-related injuries and infections.

Neurosurgeons performed numerous operations to relieve the pressure in Shannon’s skull, along with a pioneering procedure that involved removing a piece of bone from her head and keeping it ’alive’ in a pouch in her stomach so that it could be later returned.

It took many months of rehabilitation before Shannon was deemed well enough to leave the hospital. She now lives with an acquired brain injury, an invisible disability that has left her with cognitive fatigue and hypersensitivity to sound. But during those long months, moving in and out of coma, Shannon was taking notes and recording her experiences. When she left, she took with her a huge sheaf of personal and medical records. She wanted to do something with her experience, something visceral and personal, something more than simply writing about it.

She began working with Anna Newell, a theatre director, who then contacted me. Shannon knew that whatever the project turned out to be, sound would be an important element, as hearing was one of the senses that remained with her throughout. Even in a state of coma or under anaesthetic, she could still hear.

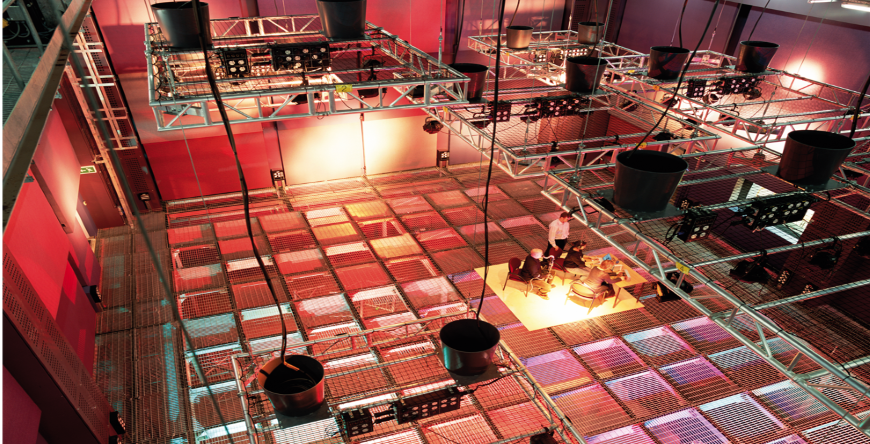

Several years of research and feedback followed. From them, slowly emerged the work Reassembled, Slightly Askew. It’s an immersive piece that the audience experiences individually, lying on a hospital bed while listening to the audio via headphones. The audio technology makes the sound three-dimensional, causing listeners to feel they are inside Shannon’s head, viscerally experiencing her descent into coma, brain surgeries, early days in the hospital and reintegration into the world with a hidden disability.

The reaction to the piece has been incredible. Since our first draft performance in Belfast in 2012, we have taken it all over the world, to Hong Kong, Canada and to the Mount Sinai Medical Centre in New York, where we received a rave review in the Wall Street Journal. Reassembled has also acquired an unexpected dual life: it works as both an art and as a medical training aid, helping medical professionals understand what their patients are going through. It seems to cut across all kinds of audiences.

Throughout human existence, the arts have always played a powerful role in how we narrate our world, particularly in amplifying the voices of those who aren’t always heard in society. First and foremost, we always set out to create an excellent piece of art. If you do a good job of that, it can be transformative and transporting.

Professor Laura Lundy, Co-Director of the Centre for Children’s Rights, Professor of Children's Rights at Queen’s University, Belfast says that we must do more to take children's views seriously on the matters that affect them.

For more than 30 years, there has been an international obligation on governments to make sure they seek out children’s views and take them seriously, under Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Our research in the early 2000s discovered that this simply wasn’t happening. Children’s views were neither sought nor taken seriously. It wasn’t just that adults didn’t want to do it – they often didn’t know how to do it well.

There was much talk about ‘the voice of the child’ and how important it was. But reality didn’t match up to the human rights obligation. It was clear that ‘voice’ was not enough – in fact, the way that this abbreviation was operating was actually undermining children’s right to be heard. There was little consideration of what the children were actually saying, or an understanding of the obligation to act on it.

So, in 2005, I wrote a paper called ‘Voice’ is not enough that set out the Lundy Model – though it wasn’t called that in the beginning! I never set out to create a model. I just wanted something practical, that could be legally sound (I’m a lawyer) and user-friendly. But it’s had a phenomenal impact, beyond anything I ever imagined.

The Model has four concepts: space, voice, audience and influence. Space is about providing a safe and inclusive space where children are comfortable saying what they think – this might involve, for example, creating a confidential way for them to express themselves.

Voice is ensuring that children understand the issues that affect them: sometimes we need to support them with good information in child-friendly language. Audience means that if you’re gathering children’s views, you must ensure they are going to the right people – those who have the power to act. And influence is about taking children’s views seriously and acting on them.

I have been working with the Irish government on child participation since 2012 – they named my approach the Lundy Model. It was subsequently taken up by the European Commission, the World Health Organization and governments all over the world. I have also been working with the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child to make sure that children’s views are taken seriously at the UN. Children are the majority population in some countries, and we have seen an increase in youth activism across the world. Yet at the UN, children have often been absent from meetings, even those discussing their rights and needs.

There’s a lot of resistance to engaging with children. When I was in law school, I admit that I didn’t buy into it fully either – I thought that the adults should be left to get on with it. But when I started to research the subject and listen to children’s views and experiences directly, I did a U-turn. We now know from experience that we cannot keep children safe if we don’t listen to them or take them seriously. Likewise, this right is crucially important if we are to deliver on all other rights for children. It is a barometer for children’s rights generally.

Top of Page